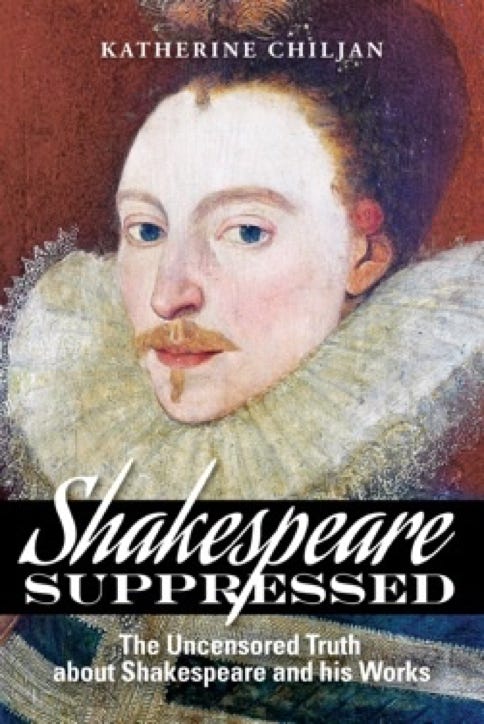

Katherine Chiljan, in her book Shakespeare Suppressed, has outlined at least 11 Elizabethan writers who refer to Shakespeare as a high-born man not given proper credit.

She also cites examples in contemporary works in which writers made fun of a country bumpkin posing as a famous writer!

There are other problems for the Stratford man to claim the title of writer - a claim that apparently neither he nor his family ever made during their lifetimes. He never left England, yet the plays are filled with specific details and little-known colloquialisms from Italy. And in 1589, writer Thomas Nashe notes that Hamlet has already been played onstage. The Stratford man was a mere 25 years old at the time, and could not have written his greatest work by then.

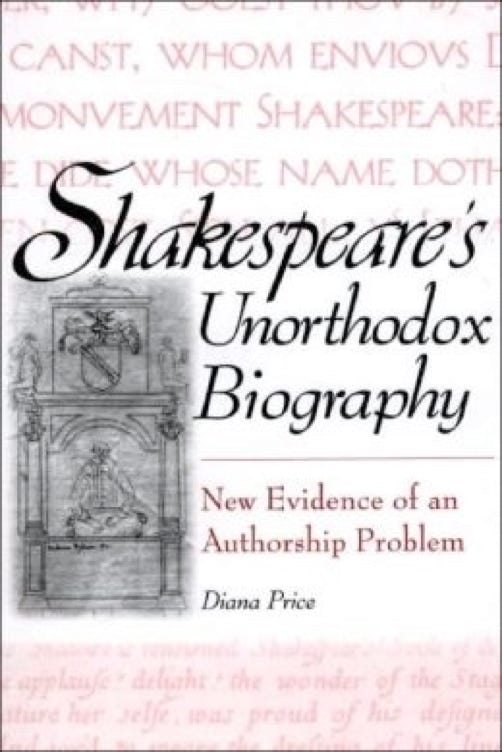

Other than a similar name, there is no evidence of a literary trail for a man named William Shaxpere (or Shakespeare). Diana Price, in her book Shake-speare’s Unorthodox Biography, has traced the literary trails of 24 authors of the period. In looking at Jonson, Massinger, Lyly, Middleton, Marlowe, Greene, Kyd, Peele, and others, she shows evidence of education, written correspondence, payments, relationships with patrons, extant original manuscripts, inscriptions, commendatory verses, ownership of books, being personally referred to as a writer, and notice at death as a writer. Most of the 24 authors appear on most of these lists. Shakespeare appears on NONE of them! When the Stratford man died in 1616, what happened in commemoration of the passing of Queen Elizabeth’s and King James’ favorite playwright was NOTHING! No ceremony, no procession, and no burial with other great writers at Westminster Abbey. Instead, he was buried at Holy Trinity Church under a stone that curses those who are tempted to dig up his bones.

For these, among many other reasons, some scholars believe that William Shaxpere of Stratford-upon-Avon was not our William Shake-speare!

Why Some Believe Shakespeare Wasn’t Shakespeare.

Ever since 1597, when Elizabethan satirist Joseph Hall published a series of pamphlets hinting that the author of Venus and Adonis shifted his writings “to another’s name,” people have questioned whether the man from Stratford-upon-Avon, known in legal documents as William “Shaxpere” or “Shagspere,” was the real author of the Shakespeare works, or whether this identification may be a matter of mistaken attribution. Numerous facts in the official story of the Stratford man lead many to ask: Was the name “Will Shake Spear” a pseudonym?

The Stratford man’s name was similar to the famed author’s, but not an exact match. In the 30 legal entries of the family name found in the Stratford Register of christenings, marriages and burials, only ONE reproduces the name as “Shakespeare,” and that's for the christening of Will's daughter Susanna, who 20 years later is married as Susanna “Shaxpere.”

Well after the fame of the author, Will's daughter Judith gave birth to a son in 1616, and in honor of her father named him “Shaxper” Quiney.